December 06, 2024

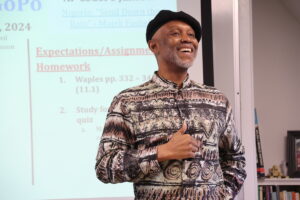

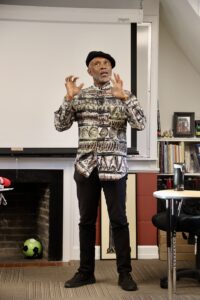

Dr. Okey Ndibe: Nigeria’s Struggles with Corruption and Resilience

Dr. Okey Ndibe, the celebrated Nigerian author, delivered a compelling presentation this morning in our Upper School Global Cities class. He delved deep into the intertwined complexities of Nigeria’s oil sector, corruption, and its broader societal impacts. These issues, he argued, form the backbone of Nigeria’s ongoing national narrative. Ndibe’s critique spanned decades of corruption and human rights violations, laying bare the challenges faced by Africa’s most populous nation.

Before Ndibe’s address, two students presented several current events in Nigeria, including the corruption in the nation’s oil industry and the government’s crackdown on pirating oil, an anti-graft case regarding the seizure of property, and a boating accident where many individuals perished.

Ndibe segued into an exploration of the legal profession’s struggles with systemic corruption, particularly highlighting the plight of Dele Farotimi, a fearless Nigerian attorney whose activism has recently captured the attention of social media. Farotimi has made waves by publishing a book exposing corruption within Nigeria’s judiciary—a move that led to significant backlash. Ndibe revealed how Farotimi’s exposé pitted him against Babatunde Babala, one of the wealthiest and most influential lawyers in Nigeria, known for his alleged use of wealth and influence to secure judicial outcomes through bribery.“Unlike America, where a sizeable number of lawyers want to stay in private practice because that’s where the money is,” Ndibe said,“in Nigeria, people lobby to be made judges because that’s where the money is.” Ndibe recounted personal anecdotes, including his youngest brother’s experiences as a Nigerian lawyer, highlighting how the expectation to bribe judges undermines the legal profession’s integrity.

Ndibe then shifted his focus to the current president of Nigeria, Bola Ahmed Tinubu. Tinubu’s rise to power, he argued, epitomizes the entrenched cycle of political corruption in Nigeria. As a former governor of Lagos State, Tinubu built an empire of influence, installing loyalists in positions of power and extracting significant revenues from the state through mechanisms like private toll companies and revenue collection schemes. Ndibe described how Tinubu wielded this wealth and power to become Nigeria’s kingmaker, ultimately securing his presidency in a controversial election.

Tinubu’s infamous declaration during his campaign—“Emilokan” (Yoruba for “It’s my turn”)—was a stark display of arrogance, according to Ndibe. He noted that Tinubu’s presidency represents a grim continuity of Nigeria’s political status quo, where corruption and impunity reign supreme.

Despite the pervasive corruption in governance, Ndibe celebrated Nigeria’s cultural contributions to the world. From literature to music and film, Nigerians have made a significant global impact. He recounted personal anecdotes of encountering Nigeria’s cultural power abroad, from the music of Fela Kuti to the international acclaim of “Nollywood” films. These moments, he said, underline the paradox of Nigeria—a country that excels in cultural and intellectual production while grappling with disastrous political leadership.

Ndibe has suffered at the hands of the government; every time he enters Nigeria, he is arrested at the airport due to his criticism of the regime. After years of writing a weekly column and hosting a podcast that critiqued the Nigerian government, he found himself at a crossroads. “I no longer either properly understand Nigeria or have anything new to say,” he confessed because of the cyclical corruption that befalls the country. This sentiment resonates with many Nigerians in the diaspora, who witness the country’s potential squandered by cyclical tragedies and entrenched corruption.

Ndibe opened the class up to questions. One student asked if he felt his journalistic articles or books were more impactful. Without hesitation, Ndibe said his articles are more influential because of their immediacy. “In a sense, you can help shape the public response to an issue,” he said. “It was my day-to-day articles that riled the government, so I was put on a list of enemies of the state.”

One student asked how Ndibe maintains his courage to keep speaking the truth. “Fear is a choice, and I’ve chosen not to live in fear,” he said. He took inspiration from a Nobel-prize-winning Nigerian writer, Wole Soyinka, who wrote The Man Died. “When there are moral issues, we ought to speak; we ought to take a stand,” he said. “Sometimes, out of moral cowardice or comfort, many of us retreat into silence. I find that I suffer profoundly when I see injustice and I can’t speak. It’s one way of dying.”

One of the last questions a student asked was regarding the ethnic divisions within the country. Due to the number of factions, she asked if Nigeria would be better off balkanizing itself along ethnic or religious lines. Ndibe takes a principled stance. “I wish for Nigeria an ethnicity of values,” he said. “I want Nigerians to begin to look at issues and say, ‘This is bad, and my judgment on this is not affected by the ethnicity or religious affiliation or the state or the tribe of the person who has committed the act. It’s either good, honorable, or dishonorable.”