October 21, 2024

Robert Calafiore: Exploring Tradition, Craft, and Human Connection through Analog Photography

Through the generous underwriting of the Goodman Banks Visiting Artists Fund, KO welcomed artist Robert Calafiore to KO. Born in New Britain, Connecticut, to Italian immigrant parents, Calafiore’s upbringing in a traditional Roman Catholic home left a deep imprint on his artistic sensibilities. His early experiences in a close-knit family environment, rich with religious influence and a strong work ethic, have informed both his creative practice and his philosophical outlook on art and life. These themes of tradition, family, and human connection are a consistent thread throughout his work.

Calafiore’s journey into the arts was groundbreaking within his family. As a first-generation American, he was the first to attend college, earning both a Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA) in photography from Hartford Art School and a Master of Fine Arts (MFA) in photography from the State University of New York at Buffalo. Currently, he serves as the Associate Dean at the Hartford Art School, where he balances his administrative duties with his commitment to teaching and his ongoing artistic practice.

Calafiore’s photography, particularly his work with pinhole cameras, is driven by a deep fascination with how technology has altered our physical relationship with the world and each other. In an era dominated by digital photography and virtual communication, his use of handmade, analog processes stands as a deliberate counterpoint to the speed and convenience of modern technological tools. For Calafiore, the physical labor involved in creating his images is just as important as the final product—an approach heavily influenced by his parents’ blue-collar background, where hard work was valued and celebrated. “I tend to like things that are really hard and laborious,” he said.” The harder it is, the longer it takes, the longer and harder it is for me to figure out a solution, the more I enjoy the process.”

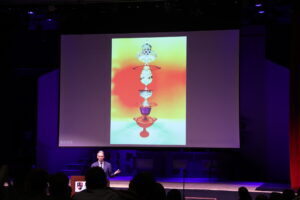

His pinhole camera series challenges viewers to consider the passage of time and the shift in how we perceive and engage with physical objects. These works, created with exposures lasting up to 80 minutes under intense lighting, are built layer by layer with carefully arranged stacks of glass, household objects, and family heirlooms. Each photograph is a one-of-a-kind creation, with no digital negatives or copies. This meticulous analog process, where even the pinhole itself is handmade, results in richly colored, large-format prints that evoke both personal memory and universal experiences of family, tradition, and materiality.

Calafiore’s early work involved traditional analog photography, where he experimented with blending the human figure into constructed spaces. Over time, his focus shifted toward creating architectural and fantastical tabletop constructions, where objects are photographed and projected to create illusions of depth and reality. “The way we interact with the things that we build and the space we are in became a driving force early on,” he said. “These constructions are fantasy spaces that are based on my interest in how we live as humans within the architecture we create.” His artistic process draws heavily from his childhood experiences, such as traveling to Sicily and being mesmerized by its ancient temples and frescoes. These influences are clear in his intricate, illusionary compositions that invite viewers to question the boundary between reality and artifice.

His work often explores the balance between simplicity and complexity, the tension between hand-crafted objects and the larger narrative they tell. For example, his “temples” series—sculptural pieces that reference religious iconography—were influenced by the elaborate altars he observed as a child in his family’s church. This reverence for the handmade and the sacred continues to manifest in his later work.

While Calafiore’s art is deeply rooted in tradition—both in terms of his subject matter and his analog techniques—it is also a meditation on the future. He is particularly interested in how younger generations, growing up in a world dominated by digital technology, have a different relationship with physical space and materials. He observes in his students a marked shift away from the tactile experiences of measuring, building, and crafting that once were essential parts of childhood. This change is reflected in the way his students struggle with tasks like cutting a straight line or handling physical tools—skills that were once commonplace but are now unfamiliar due to the rise of digital devices. “Now I need to take an entire day to show students how to hold that ruler, how to use the utility knife without cutting a finger off, how to measure what a fraction of an inch is,” he said.

For Calafiore, this shift is neither good nor bad—it is simply an observation that informs his work. In response, he has chosen to move in the opposite direction, creating art that appears digital but is entirely analog, handcrafted, and unique. “I take a 180-degree turn away from digital technology in my work,” he said. “I make works that look contemporary, digital, and photoshopped, but it is 100% analog handmade work with zero technologies.” His one-of-a-kind photographs defy the replicable nature of photography, forcing viewers to engage with each piece as a singular, physical object.

Calafiore presented some of his large-scale work, inspired by a decorative bowl displayed in his family’s kitchen as a child. Although a prosaic object, the piece meant much to his hardworking parents, a representation of achieving the American dream. Fiore began collecting colorful glassware bordering on obsession that is now featured in his work, either stacked on top of one another or in a collection.These photos of glassware “tell a really personal story,” he said, “and yet it’s universal at the same time. So many people have gone through the immigrant experience, and this was a way for me to use those objects and tell this story.” Although some of the pieces may be white in reality, through his painstaking set-up of lights (40,000 what’s of light!), the final image of the bowls and bric-a-brac are kaleidoscopic and mind-bending.

Throughout his time at KO, Fiore will conduct workshops with Upper and Middle School students using pinhole cameras, with the students themselves as the subjects of the photography. One of the challenges in using this photographic method is the time the subject must remain still (over three minutes!) for the camera to capture the image. That’s a tall order for some of our Middle Schoolers, but the class last week embraced the experience, particularly seeing their images develop in the emulsifying formula in the dark room.

As Robert Calafiore prepares for upcoming exhibitions, including a solo show at Kozlow Larson Gallery, his work continues to evolve. His recent series have incorporated new materials, lighting techniques, and an increasing complexity of composition, but his core interest remains the same: exploring the intersection of human experience, tradition, and the changing technological landscape.

Whether capturing the intimate history of his family through treasured objects or questioning the future of human interaction in an increasingly virtual world, Calafiore’s photography challenges us to pause, reflect, and reconnect with the physical and emotional ties that define our shared experiences.

Calafiore’s work has been exhibited extensively, both nationally and internationally. He is represented by ClampArt Gallery in New York City and Kozlow Larson Gallery in Houston, among others. Recent highlights include being named the Second Sight Award winner at the Photo Fair in San Francisco and being featured at the Medium Festival of Photography in San Diego. His photography is held in private collections and museums across the country, including the New Britain Museum of American Art.

In addition to his gallery work, Calafiore advocates for arts education, emphasizing the importance of creativity in all fields. In his public talks and classroom teachings, he stresses that arts education is not merely about producing artists but about fostering creative thinking—an essential skill for success in any discipline. “Whether you go into the arts or not, taking courses in the arts is about creativity,” he said. “There’s nothing better than the arts teaching about how to think outside the box and learn new solutions to old and reoccurring problems,” he said.

Arts

News Main News